The UK energy market is something of an enigma – it is a heavily regulated oligopoly masquerading as a competitive market.

Amidst the remains of failed energy firms, bizarrely designed maximum prices, bans on acquisition pricing, spiralling bills and toothless regulators, is the result of what can be deemed a big experiment in what happens when you privatise an essential utility.

Like water, you don’t get a choice about whether you want to use the UK energy network (unless you live in one of the few properties that uses oil tanks) and as in the water industry, we are slowly learning that privatisation and consumer protection don’t always go hand in hand.

There has been endless documentaries and news reports about the mess that has been made by privately owned water companies (both literally and figuratively) yet until a recent Energy and Net Zero Select Committee inquiry last week, little had been said about the state of the energy market.

This is mostly because, unlike water, there is at least the illusion of competition in the energy market and for many years Britons have heeded the rallying call of Martin Lewis to “ditch and switch” to get a better deal which worked perfectly well…until it didn’t.

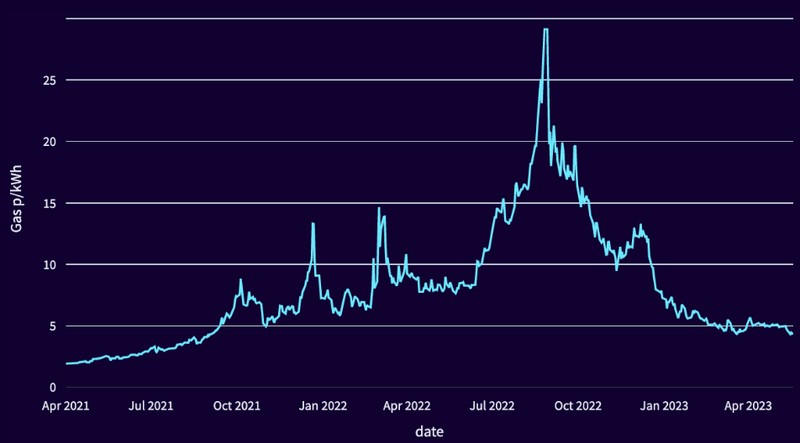

Cast your minds back to 2022. Russia had just invaded Ukraine, Liz Truss found herself as Prime Minister (briefly) and due to a combination of these factors, the energy market was in turmoil.

The war in Ukraine and subsequent sanctions on Russian oil had sent global energy prices into a tailspin and many Britons were looking at the dire choice between heating and eating.

However, fear not, we had Prime Minister Liz Truss (words that I am sure have never been typed before) who planned to spend £120 billion on capping household energy bills at £2500 in order to protect consumers in a scheme known as the Energy Price Guarantee (which worked in the same way as the Price Cap).

We already had the Energy Price Cap which caps the rate at which energy is sold (not the total bill contrary to what many believe) but this merely tracks the wholesale rate and was set to be above £4000 for a typical user – not something many could afford.

As such, everyone paid the Energy Price Guarantee rate, even if you had taken out a fixed deal you still paid that price. This was great for ensuring that consumers were not bearing the brunt of soaring wholesale energy prices but it turned out to be the nail in the coffin for the UK having a competitive energy market.

The implementation of a maximum price meant that suppliers were unable to pass on the higher wholesale energy costs onto consumers and had to absorb this cost themselves and let it eat into their profits. The energy giants (British Gas, Eon, npower and EDF) managed this fine, the smaller suppliers did not.

Between July 2021 and July 2022, 29 energy suppliers failed which affected 4 million households whose energy supply was shifted to another firm which had the effect of making the incumbents even larger.

Amongst the smaller casualties was Bulb, an energy disrupter that was the cheapest for a long time and had built up a strong customer base. However, they failed to hedge against spiralling energy prices effectively and collapsed at a cost of £6.5 billion to the taxpayer (according to the OBR, the then government disputes this figure).

What happened to energy in 2022 was unprecedented but it is the legacy of this situation which is of gravest concern. In our supposedly competitive energy market, around 70% are on a price-capped regulated tariff (source: MoneySavingExpert.com) and those who are not have saved little from entering into the competitive market.

The lack of competition has not been helped by the energy market’s perennially inept regulators: Ofgem and the Energy Ombudsman.

The latter has no statutory powers therefore their decisions are not legally binding and firms have no incentive to improve their customer service (although this has helped Octopus Energy who pride themselves on good customer service and are now the UK’s third biggest firm).

The former seems to have done everything in their power to make the market less competitive. The price cap was needed and protects vulnerable customers (to an extent) but has made people even more apathetic and their ban on acquisition pricing (charging new customers less) has meant that there is no incentive to switching hence why so many people are on the price cap.

This then poses the question as to how best to sort out the mess that is our dysfunctional energy market. In my view, there are two options (other than doing nothing): allow energy to be a free market (to an extent) or renationalise.

Let us discuss what the first option would entail. I would propose that we abolish the price cap and allow acquisition pricing but retain a level of regulation that protects the most vulnerable but also allows the market to be a functioning market.

This intervention would involve giving the Energy Ombudsman statutory powers to ensure that providers do provide proper customer service (although there is an argument that the incentive of attracting customers in a free market would do this anyway as it is a means of differentiation) and introducing social tariffs.

This last point is similar to what we have in telecommunications: special deals for those on certain benefits to ensure that they are not exploited by the market. In my proposal for energy, this would also be expanded to the elderly as it is probably unreasonable to expect all pensioners to be au fait with price comparison sites.

Everyone else would be expected to fend for themselves. If you want to pay less for your energy, spend half an hour on a comparison site and find yourself a better deal, if you can’t be bothered to do that then be content with your higher price.

As someone who has spent the best part of 10 years learning about personal finance and now campaigns for financial education, the idea of putting consumers out to dry appalls me on a personal level but I see it as the best option as long as there is some level of information provision about how to get the best deals (finally a use for the Money and Pensions Service beyond sorting out pensions?).

The alternative is to renationalise energy. This would ensure that all consumers pay a fair price and that people are treated fairly (one would hope) but this is a completely unrealistic scenario. The cost of buying up shares of every energy company would be astronomical (even greater than that for water) and I do not think that it would be to the benefit of the majority of consumers therefore not justifying the expenditure.

But what about GB Energy I hear you ask? (probably only Ed Miliband would say that actually) For those who aren’t Ed Miliband, GB Energy is the Labour government’s answer to the energy problem by providing a state-backed firm.

I feel that this adds to the problems we have in energy, the market is dysfunctional because there is no competition and it is in the unhappy medium of trying to be competitive while being heavily regulated and adding in the complexity of GB Energy will only make this worse.

The government has stated that they hope to use many of the over 80 regulators to liberate their markets to generate growth – if anyone vaguely related to the corridors of power is reading this, can you do this to energy first?

Do comment your thoughts below.

Leave a comment